- Home

- Kevin Sampsell

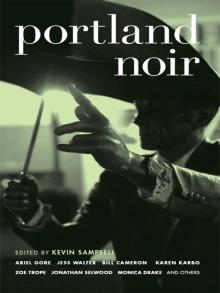

Portland Noir Page 3

Portland Noir Read online

Page 3

“Why don’t you sit down and I’ll get it.”

She pulled her hair out of its scrunchie and pulled it back up on top of her head. She didn’t sit down.

I took my time. I walked down the long hallway to my bedroom. I sat on the bed in the dark. It occurred to me that Agnessa was going to need someplace to put her clothes. I didn’t have a bureau, but instead used the top two shelves in the closet. I walked back down the hallway. Charlotte wasn’t there. From the kitchen I could hear the freezer door open, then Charlotte’s loud laugh. Ha!

I stood in the middle of my front room, stared at a poster I’d taken from our old house, black-and-white, a young couple kissing on a Paris street. It had some name in French.

“This wasn’t something I wanted to tell you over the phone, but one night someone broke into my flat in Prague and stole your ring,” I called into the kitchen. I was glad not to have to look her in the eye. “They took my wallet too. And my passport.”

She came back into the living room holding the frozen top layer of our wedding cake. “I can’t believe this.”

“It’s our wedding cake,” I said.

“Yeah, I know what it is. How is it you still have it?”

“You said I could take anything I wanted.”

“What did you do with it for the two months you were in Prague?”

“I got a sentimental streak a mile wide, so sue me.”

She started shaking her head. She shook her head and laughed. Laughing and crying, mascara running. “At first I thought Elaine was the nut job, but it’s you! I didn’t believe her when she said you didn’t even go to Prague. It was impossible. No one is that crazy. She said if I didn’t believe her to check the freezer.”

“Elaine is a nut job,” I said. “She thinks she’s a witch.”

“Stop, Ray, just stop.”

“She wanted to put a spell on you but I wouldn’t let her.”

“You’re out of your mind.”

“The guys broke into my flat when I was out one night with Agnessa,” I said. “You wanted the truth and this is the truth. I’m in love with Agnessa.”

“The girl who lives with her parents and likes stuffed animals?” She put the wedding cake on the table so she could cross her hands over her chest like she does and throw her head back, the better to laugh her guts out. She was lucky I didn’t throttle her right there and then.

I said that I strolled across the Charles Bridge with Agnessa, and admired the astronomical clock with Agnessa, and that Agnessa’s family actually owned the Clown and Bard.

She said, “God, Ray, could you be a bigger loser?”

I stared at her. She wasn’t supposed to say that.

“That’s a rhetorical question, by the way.”

She stalked down the hall to the bathroom to find some tissue to wipe her eyes. I followed her, and when she turned around I grabbed her by the neck and gave her a good shake.

Grabbing a woman by the arm is a loser’s game. They throw your hand off and shriek, “Don’t touch me!” and act as if you’re some low-life abuser. I just needed her to shut her up, and the neck is the pipeline to the mouth. I will admit that after she got quiet, I tossed her against that scalding-hot water pipe just to get my point across. So sue me.

Back in the kitchen, I put the frozen wedding cake back into the freezer. I looked out the window. Down on the street a girl rode past on her bike, the flakes setting on her hot-pink bike helmet. Portland is cold enough to invite snow but too warm to keep it. It has something to do with the Japanese current. Charlotte could tell you, but she isn’t coming out of the bathroom anytime soon.

The snow stops like I said it would. I put on my Vans and locate my passport in the top drawer of my desk. Outside, the air feels good on my arms. The back of my neck is nice and cool. The forced-air heat was way too much in that place. In the parking lot I pull the plates off my truck, crunch across the snow, and stuff them into the dumpster behind Esparza’s. Just as I’m closing the lid, I hear the slow koosh-koosh of bald tires on snow and look up to see the art car rolling down the street. I tell you, I’ve always been lucky.

At PDX I call the phone company to turn off my service. I’m doing Agnessa a favor. I only want the best for her and it’s best for her to go with the guy with the multiple TVs. Then I call 911 and report an intruder. I give my address and tell them its right across the street from Noble Rot, where wine is a meal. Then I buy a ticket for the next plane out. Like I said before, I’m a simple guy. I take life as it comes.

JULIA NOW

BY LUCIANA LOPEZ

St. Johns

There was a photo pasted under the wallpaper, next to a note written on the wall. Dear Julia, We both know the truth. RIP. Henry.

“What’s that?” Josh asked.

“I don’t know,” I said. Josh was wearing his painter’s pants, even though we weren’t planning to start painting for a while yet. There was no furniture in the dining room either, just the two of us, peeling off the old, faded wallpaper, a sort of peach brocade. We’d only just moved into the blue bungalow a week ago, in St. Johns, the only Portland neighborhood left where we could afford a house that wasn’t already occupied by wildlife.

Josh read the note aloud, then whistled through his front teeth. He took the photo from my hands to inspect it. A woman, a little plain but not actually ugly, glared back at us, standing at a kitchen sink—our kitchen sink—in a blue housedress, a cigarette dangling between her lips. She’d turned her head to look at the picture taker, and except for those fierce dark eyes, her face showed no expression.

“Guess they lived here before us, huh?”

I rolled my eyes. “Thank you, Captain Obvious.”

He shrugged, then kissed my nose. We’d been together five years. My mother was dying for him to propose; somehow marriage never seemed to come up between us. Buying the house together had been his idea.

“RIP. So she’s dead,” I said.

Josh laughed. “That’s usually what it means, yeah.”

“There’s a date on the back of the photo. August 8, 1957,” I read. Josh had already turned back to the wall, tearing off wide strips of the paper. Small frayed fragments dusted his brown hair, like bits of lace floating down. One landed in his eye, and he wiped his face with an impatient motion. Peach dust turned his brown hair pale.

I like to go running at night, after dark. Josh had joked once that I’d make a great mugger, the way I like to stay quiet and jog past at night. This was my first run in St. Johns. We lived a few blocks off the neighborhood’s main drag, so we hadn’t seen much else of the area. The sun had just set awhile ago, and the orange light was fading, streaking into dark blue out in the west. I set off with no particular direction in mind, just turning and turning and running down whatever street caught my eye. Some of the houses here were quite nice, big and roomy and expensive-looking. Many were like ours: tidy, modest, with well-kept lawns and painted trim, sometimes with roses or other flowers growing in the garden. Up-to-date. Important enough for someone to care about. They were small, but there was pride of ownership. I liked to see those houses.

Some were small and unkempt; dirty or peeling paint, weed-choked yards, fences missing slats. These houses looked old, and tired. Longtime residents, probably. People who’d lived here since it had been a working-class neighborhood, blue collar, the kind who lived paycheck to paycheck.

Portlanders have fuzzy bunny reputations as liberals, knee-jerk tree-huggers, and soft touches. But now that Josh and I owned our place, our house, I found myself looking at the rundown buildings with a more critical eye. How easy it would be to, say, mow that lawn, or to tear out that tacky fence. The fake tiki torches, or the sagging porch. Why don’t these people do something about this? I was breathing easily now, in the middle of my run, the place where I feel I can go forever, until suddenly I can’t. I passed a couple arguing in the street, the woman leaning out of a rusted car with plastic over where the rear passenger window should be.

Then a woman pushing a baby stroller. Kids riding their bikes in the street. On my left was a store selling tobacco products; on my right, across the street, a small Thai restaurant with a buzzing neon sign.

This neighborhood could be so great, I thought, with just a few fixes. Once it had been considered too far from downtown for people like Josh and me to consider living here. But it was only about seven or eight miles—not so far, after all, as people discovered when the real estate boom meant a starter home in close-in neighborhoods went as high as $300,000 or $350,000. In the 1800s, St. Johns had been a separate city, but got absorbed into Portland in 1915. In many ways it still felt like a separate place, tucked into an odd triangular corner of the city’s north end. It was awkward to get here, either through an ugly industrial area on the Southwest side, or through a stretch of commercial road and trucking companies on the opposite. The lack of scenery made it feel a bit cut off in some ways.

It could all be so great here, I thought. We can make this place really special. It could always have been special, but maybe now was its time.

I felt the pounding rhythm in my knees. A big black dog barked from a yard, behind a chain-link fence. I smelled roses from a nearby garden. Another batch of kids on bikes waved to me. “Hey, runner,” they called out. “Hey,” I called back, puffing just a little.

The next day I woke up with their names on my mind, where they stayed as I brushed my teeth and took my shower and combed my hair and got dressed. At our breakfast table, still the same beat-up oak hand-me-down from our apartment, I looked over at Josh as he read the paper. I could see the headline; a new Starbucks had gotten its windows smashed in, way over in Southeast. St. Johns had a Starbucks too, but it was hard to imagine anyone caring enough to vandalize it. “Henry and Julia,” I said aloud, “Who do you think they were?”

He looked at me for a second around the Metro section. He was already wearing a suit and tie, his white shirt crisp and starched. I wore faded jeans and a puffy white peasant shirt. He was an accountant; I was a bike repairwoman. That’s how we’d met—I’d stopped to help him fix his bike on the side of the road one day, got it patched up after he got run off by an SUV. Even in Portland, probably as close to American bike nirvana as there is, that sort of thing happens.

“Probably just people who lived here before,” he said. “It was fifty years ago; they’re probably dead by now.” He gave me a wry smile to take the edge off his words and went back to his paper. I grabbed the front section of the paper and read it as I ate my cereal. It had taken us months of living together before we could simply be silent in each other’s presence, and now I relished the velvety quiet between us. Josh was thirty-two and I was twenty-seven. I was 5'2 , he 6'2 , so much taller than me that his big toe was the same length as my pinkie finger. At night he liked to smell my hair, inhaling deep into his lungs, before falling asleep. It made me feel like he wanted all of me, even my scent, loved every bit about me.

I rose from the table first and kissed him goodbye. We used to live downtown, where our commutes were each less than a mile. Now we were more like seven or eight miles from our jobs. Josh drove, so it wasn’t long for him, but I biked, riding south along the Willamette River until I crossed the water into the Southwest side. It was beautiful now that it was the summer, crisp, humidity-free weather with a vault of clear blue sky above. In the winter, in the rainy season, well, I’d probably bike then too. I was stubborn that way.

Henry and Julia. Henry and Julia.

I was early at the bike shop. Truth be told, I’d known I was setting out too early from home. This way I could kill some time at the library.

The downtown library branch was only a few blocks away. I locked up my bike and strolled over. The building was imposing, stone and red brick, tall and grand. I’d always been proud of Portland for having a place like this, even if I didn’t use it a lot myself. It made me feel like we were a real city, a real, important place.

The reference librarians sat behind a massive desk on the first floor. There were three people there now: an older woman, a middle-aged woman, and a cute guy with red hair and gold wire-rimmed glasses. I walked up to the desk, but before I could get the cute guy’s attention, the middle-aged lady glanced up at me.

“I’m looking for information on some people,” I blurted out. I was cracking my knuckles now, an old nervous habit, and the pops sounded crass to me in the silence of the room.

“Which people?” she asked. I realized how stupid my answer—Henry and Julia—would sound.

“Well, maybe a place would be better to start,” I said. “My house. I mean, the house I just bought, but the people who owned it before me. Us. Who used to live there.”

Maybe I should have told Josh what I was doing. Maybe he already knew. When I was a kid I’d been the one to touch the poison oak to see if it was really that bad; it was, but the physical itching still burned less than my curiosity had.

The woman took down my address and suggested a few places to start—county property and tax records, some property websites, even, she suggested, the Oregonian archives, our daily paper. “How far back do you want to go?” she asked.

“August 8, 1957,” I replied.

She nodded, as if unsurprised. “This could be tough. Those kinds of records can wind up all over the place.”

I thanked her, said goodbye, and headed off to work. Josh would already be in the city by now, I thought to myself. Josh and Allison. Not quite the same ring as Henry and Julia, but nice in its own way, I thought.

Over dinner that night, I told Josh what I’d done. “She said it might be hard, but possible. But that maybe I’d have to do some digging.”

Josh put down his fork with a sigh. He’d made apple-stuffed pork chops and baked potatoes; I usually dated guys who liked to cook, since, left to myself, I’d have peanut butter and jelly sandwiches for dinner every night. “Allison, we just got here. Can we maybe work on the house a bit first, maybe do some of the renovations and changes we talked about before you go flitting off into something else?”

I could feel my brow furrowing, and I tried to smooth it out. I know he hates it when I get, as he puts it, pouty; I wanted to make him happy. “But don’t you want to know who these people are? What the truth is? All that? I mean, maybe there’s Spanish doubloons buried in the backyard! How cool would that be?”

“Honey, we just got here, we have so much to do. Why waste your energy on this?” He was in sweats by now, though I still wore the same jeans and blouse as earlier in the day. Across his sweatshirt was written, in gold, Minnesota. My mom loved that he was a Midwest boy. I didn’t care either way. He grinned, his perfect teeth lined up like a picket fence. “And anyway, maybe Julia’s the one buried in the backyard.”

“My point exactly. Wouldn’t you want to know that?” I asked, pointing my fork at him. A tiny sliver of apple fell off the tines onto my plate. Josh reached out with his own fork, speared the apple slice, and popped it into his mouth. He didn’t speak until he’d swallowed it.

“No,” he answered. “I really wouldn’t.” He went back to his pork chop, and the sound of his chewing filled our small kitchen. Beneath the table, though, I felt his foot slide across to mine and rub the inside of my arch. His bare foot was warmer than my own, and I rubbed his foot back.

It took me three weeks of running back and forth among county agencies. One place had ownership records, but not on computer, so I had to go request the file in person. Henry Lewis, it turns out. The house was in his name alone, so I tried tracking down a marriage certificate for him—Julia Crosby, Julia Lewis after 1951. Henry had owned the house until only ten years ago, when someone had bought the place and moved in. Then it had been sold again, a year ago, renovated, and sold to us. So few people separated us from Henry and Julia.

There wasn’t much other information about them in the county files, no matter where I looked. Maybe they had simply led quiet, unassuming lives, I thought. Then I remembered what the librarian said, and

checked the newspaper archives. The electronic records didn’t go back to the ’50s, only the ’80s, so I had to go to the paper in person. The Oregonian’s building sits at the south end of downtown. It looks like a holdover from the ’70s, from that moment in American architecture when all taste seemed to have left us as a nation. Plain and squat and industrial looking, and no better inside, where nothing seemed to be of any particular color.

But I found Henry Lewis in the records stored there. And I found Julia Lewis. She’d been killed by a burglar, the newspaper said at first, coshed on the head. She’d bled to death on her kitchen floor. My kitchen floor. Then: Husband arrested for murder of wife. Then, a few days later, a brief, brief story: Henry Lewis had been released. Police had nothing to say; they let him go. And Julia Lewis’s name disappeared from history. If they had known back then who killed her, the newspaper never mentioned it. If Henry Lewis had been guilty or innocent, they never said. Only that she was dead, and he was released.

“Let it go!” Josh yelled at me from the bathroom. “Just let it go! She’s dead fifty years, he’s probably dead somewhere too. Just let it go and forget about it!”

I’d been talking about Julia and Henry for the past month now, since I’d discovered her murder. She stayed on my mind. I’d put her photo on my nightstand. Every day, her face looked up at me when I groped for my glasses.

“You’re not Nancy Drew,” he said. He was in socks and pajama bottoms, standing in the hall outside our door, kitty-corner to the bathroom door. There was only one bathroom in the house so far, but we planned to change that, to put in a half bath, maybe a full bath. Our contractor said that would increase the house’s resale value.

“I’m not trying to be Nancy Drew,” I answered. I was in bed, sitting up, with the newspaper on my lap. We never had time to read the paper in the morning, when it was delivered. Who does these days, anyway? “I just want to know more about them.”

Portland Noir

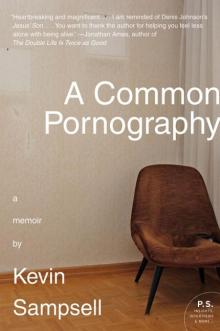

Portland Noir A Common Pornography: A Memoir

A Common Pornography: A Memoir